Around Agra Cantt railway station or along Yamuna Kinara Road, you must have seen small children picking scrap plastic. Every few minutes, they lift a chemical-soaked rag to their noses, as if that toxic vapour is their only relief.

Near reputed schools in the city, whispers of ‘pudiya gangs’ circulate. Beer and liquor have become routine at weddings and birthday parties. Some gulp cough syrup, others chew tobacco, swallow tinctures or cheap intoxicants. Bodies worn out, eyes vacant, minds adrift—these children rummaging through drains and garbage heaps are searching for a future that is already slipping away.

When a 12-year-old touches a narcotic substance for the first time, it is not mere curiosity; it is the beginning of society’s collective failure. A school uniform, a backpack slung over the shoulder, dreams in the eyes… and a vaping device in the pocket, or a pill passed on by a friend. This is no longer an exception. It is becoming the frightening new normal.

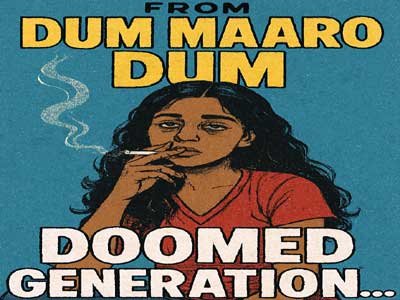

The film Udta Punjab once warned us that drug abuse was not the tragedy of a single state. It was an alarm bell. We dismissed it as cinematic exaggeration. Today, that same story is being replayed across the country, with new characters and new victims. From Mysuru’s industrial belts to Goa’s beaches, from metropolitan campuses to small-town colleges, the web of drugs is tightening.

A comprehensive 2025 survey sharpened the picture. In a study of nearly 5,900 school students across ten major cities, over 15 per cent admitted to having tried some substance at least once. Ten per cent had used it in the past year; seven per cent in the past month. The average age of initiation: 12.9 years. This should be the age of cricket, comics, and carefree laughter. Instead, it is becoming the age of nicotine, alcohol, and opioids.

After tobacco and alcohol, pharmaceutical opioids are rising rapidly. Cannabis and inhalants have found their way into schools and colleges. A 2019 national survey estimated 31 million cannabis users in India, with opioid consumption showing a dangerous surge over the past two decades. These are not just statistics. They are the silent shockwaves in homes where parents realise, often too late, that their child has changed.

Campuses have emerged as the most vulnerable hubs. Academic pressure, anxiety about unemployment, the glitter of social media, and peer influence combine to push young people toward experimentation. In elite private institutions, access and resources make it easier. But the crisis is not confined to the affluent. Small towns and government schools are witnessing the same alarming spread.

Goa offers a stark warning. Behind the glitter of tourism, narcotics worth ₹78 crore were seized in 2025, with 206 arrests, including 32 foreigners. The value of seizures rose by 700 per cent. Suspicious student deaths at a reputed engineering campus in Goa revealed that synthetic drugs like fentanyl and LSD have breached academic walls. This is not merely a law-and-order issue. It is a social and moral emergency.

Another silent shift is underway. Drug abuse is no longer confined to boys. Recent studies indicate rising pharmaceutical opioid and inhalant use among young women. Stress, depression, relationship pressures, and body-image anxieties are quietly driving many toward pills and chemicals. Social stigma keeps numbers underreported, but the ground reality is far more grave.

Vaping and hookah have become new gateways. Marketed as ‘safer alternatives’ with attractive designs and flavoured cartridges, vaping devices are alarmingly popular among teenagers. Despite bans, e-cigarettes continue to reach schools and colleges. Hookah bars, under the guise of socialising, introduce youth to nicotine and sometimes stronger substances. Even where prohibited, the business survives underground.

Most disturbing is the professional and industrial scale of supply networks. In January, a clandestine drug manufacturing unit was busted in Mysuru’s Hebbal industrial area. Narcotics worth nearly ₹10 crore, large quantities of precursor chemicals, and cash were seized. The unit had been active since 2024. Earlier, a similar factory was uncovered in Maharashtra. Cities known for culture and education are quietly becoming production hubs for synthetic drugs.

The consequences are far-reaching: falling grades, dropouts, mental instability, petty crime, and at times, sensational deaths. Families lose trust, communities feel unsafe, and healthcare systems come under strain. International syndicates and local networks together prey on vulnerable youth.

India prides itself on its youthful population. We celebrate it as a demographic dividend. But if this generation sinks deeper into addiction, that dividend could turn into a demographic disaster.

The response cannot be limited to police action. Mandatory campus counselling, accessible mental health services, open dialogue between parents and children, and sustained awareness campaigns at the school level are essential. Drug abuse must be understood not only as a crime but as a social illness demanding collective responsibility.

Today, the laboratories of Mysuru and the beaches of Goa confront us with reality. The question remains: Will we wake up, or continue watching another generation disappear in smoke?

Related Items

Shifting syndrome afflicts Agra, A city forever on the move…

Should India's small rivers and streams be left to die?

Tariff relief sparks new life in Textiles, Seafood, Jewellery and Leather sector