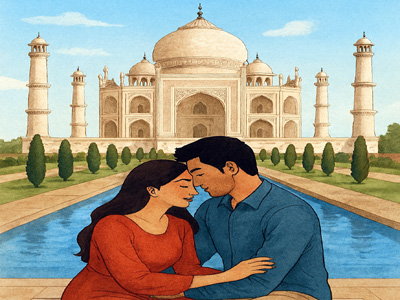

A 17th-century masterpiece, the Taj Mahal stands as an eternal symbol of love, built by Emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his beloved Mumtaz Mahal. Its unparalleled beauty and historical significance have made it a UNESCO World Heritage Site, attracting millions of tourists from around the globe.

However, recent controversies surrounding its secular character have sparked debates, raising questions about whether this monument of love is being dragged into the pit of communal politics.

The Taj Mahal has long been regarded as a secular monument that transcends religious boundaries, symbolising universal values of love, peace, and unity. Yet, in recent years, it has become a battleground for religious factions seeking to claim its legacy.

Incidents such as barring a tourist dressed as Lord Shiva from entering and prohibiting a Hindu saint carrying religious symbols have fueled tensions. These events have angered Hindutva factions, who argue that claims of minority ownership undermine the monument’s secular status.

The roots of this controversy can be traced back to historian PN Oak’s book, ‘Taj Mahal: The True Story’, which claims that the monument was originally a Hindu temple built by Rajput kings. While leftist historians have dismissed this notion, such claims, though baseless, have contributed to the communalization of the Taj Mahal, threatening its secular character.

The Archaeological Survey of India, the custodian of the Taj Mahal, has consistently maintained that the monument is a secular property, emphasising its historical and architectural significance over any religious interpretation. The Braj Mandal Heritage Conservation Society has repeatedly stated that the ASI’s role is to preserve the monument as evidence of human creativity and cultural heritage, not as a site for religious rituals or communal activities.

However, the increasing presence of religious rituals at the Taj Mahal, from prayers to worship and Ganga water offerings, has raised concerns. These activities, organised by certain groups, appear to be attempts to transform the monument from a symbol of unity into one of division. The annual Shah Jahan Urs, during which a ceremonial sheet is offered, has also grown in scale and length. The sheet, which was once four yards long, now exceeds a thousand meters. For three days, the ASI even allows free entry. While such activities reflect India’s cultural diversity, organisers should not be allowed to weaken the monument’s secular essence.

The communalization of the Taj Mahal poses an emerging threat to its status as a global tourist attraction. Agra’s tourism industry, heavily reliant on the monument, has expressed concerns over the ongoing disputes between Hindutva and Muslim groups. Industry leaders fear that such tensions could deter tourists, tarnishing the monument’s reputation as a symbol of love and beauty. The significance of the Taj Mahal lies not in its religious affiliations but in its universal appeal as a monument to love and human achievement.

Allowing communal activities at the site risks alienating communities and undermining its inclusive character. Global heritage sites like the Taj Mahal belong to all of humanity, transcending communal boundaries and promoting the spirit of shared heritage. Preserving the secular credentials of the Taj Mahal is not just a matter of historical importance but also a moral imperative. It serves as a reminder that love, beauty, and art are universal values that unite us, regardless of our religious or cultural backgrounds.

By protecting the monument from communal branding, we honour its legacy and ensure that it remains a source of inspiration for future generations. The Taj Mahal is not just a monument; it is a testament to the enduring power of love and the shared heritage of humanity.

Related Items

Love etched in marble, Blossoming on screens

World Cinema to converge in Pune with Guru Dutt’s legacy

Why is the World no longer listening to Uncle Donald…!