MGNREGA has played a crucial role in combating poverty. If 250 million people have risen above the poverty line, rural employment schemes have been instrumental in this revolution, although better implementation and corruption-free execution could have made it even more effective.

It is also evident that cash flow in rural areas has increased, leading to slight improvements in living standards. Over two dozen government schemes are acting as engines of change. Southern states, Madhya Pradesh, and Gujarat have made significant progress in poverty eradication through better implementation of rural schemes. States like Bihar, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, and Jharkhand are striving to catch up in this race.

Read in Hindi: ग्रामीण परिदृश्य बदलने में मनरेगा का रहा है अहम योगदान

The free ration scheme, which began as a necessity during the COVID era, is still ongoing and has emerged as a strong buffer or shock absorber. In the coming times, the definition of poverty will need to change. Poverty no longer resembles the scenes depicted in Satyajit Ray’s films; instead, urban slums and shanties now house people who can afford mobile phones, TVs, motorbikes, air conditioners, and other amenities.

Twenty years ago, India’s social security campaign began with schemes like ‘Antyodaya’ and ‘Food for Work’, initiated by the Janata Party. In 2005, it became a legal right through MGNREGA, i.e. Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. However, the question now arises: Have recent policies of the central government wounded the soul of this scheme?

MGNREGA, once a lifeline for the rural poor, promised 100 days of employment per year to every rural household, to be provided within just 15 days of demand. But the government’s decision to cap spending at 60 per cent for the first half of the financial year 2025-26 has put the scheme in serious jeopardy.

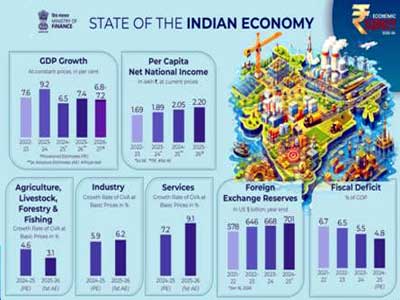

This scheme was not limited to providing wages. It also supported agriculture by building essential infrastructure like water conservation systems, irrigation facilities, and roads in villages. Yet, in recent years, the condition of the scheme has deteriorated. Its share of the total budget is now only 0.26 per cent of GDP, while experts recommend increasing it to 1.7 per cent.

The biggest crisis is the delay in wage payments. By March 2025, ₹21,000 crore had been spent just to clear old dues, leaving no funds for new wages. Workers often wait one to two months for their wages, forcing them into debt.

Additionally, daily wage rates are embarrassingly low—₹202 to ₹357 per day—based on inflation rates from 2009. Experts have repeatedly demanded the adoption of 2014 as the new base year, but the government has ignored these calls. Wages should be determined under the Minimum Wage Act. Low wages are one of the reasons migration from villages to cities has not stopped.

On average, each family receives only 50 days of work per year. The promise of 100 days is fulfilled for only seven per cent of families. Clearly, there is a huge gap between policy and reality.

To curb corruption, technical measures like Aadhaar-linked payments and attendance through mobile apps have been implemented. However, these measures exclude the truly needy—elderly, illiterate, and those without smartphones or internet access. The role of gram panchayats has also weakened. Social audits, once an effective monitoring tool, have now become mere formalities. In states like West Bengal, political tussles between the centre and state governments have left workers without jobs or answers.

Reports of large-scale corruption in MGNREGA have surfaced in several states. But investigations seem to depend on political motives—action in some cases, silence in others.

Bihar’s public commentator Prof Paras Nath Chaudhary warns that if this situation persists, farmers and labourers already suffering from climate change and erratic monsoons will face even greater hardships. Even during crises like demonetization and COVID, this scheme was a lifeline for rural India.

If the government is truly serious about rural welfare, it must remove the 60 per cent spending cap and restore the scheme to its original spirit—demand-based employment. The budget should be increased to at least 1.7 per cent of GDP, wage rates should be updated, and payment delays must be eliminated.

Related Items

A social revolution India has been waiting for…

Reforming MGNREGA for ‘Viksit Bharat’…

Comfort meets technology in India’s Vande Bharat Sleeper revolution