What does it mean to be a “common man” in India today? Is it an identity, or merely a lifelong compulsion to endure? In Digital India, you are not first a citizen, you are a number: Aadhaar, PAN, credit card, OTP, voter ID. Your existence is neatly catalogued, your dignity less so.

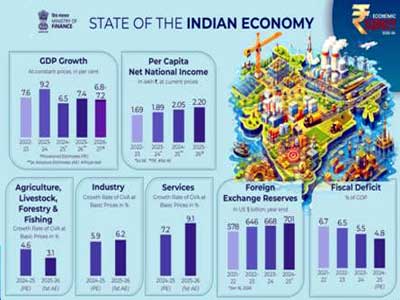

The slogan of ‘Viksit Bharat’ echoes everywhere, on hoardings, in television studios, at global summits. The macro numbers look impressive. India clocked an average GDP growth of 6.3 per cent in 2024; in Q2 of 2025–26, growth touched a heady 8.2 per cent. We are now the world’s fourth-largest economy and boast the third-largest startup ecosystem globally. To become a high-income nation by 2047, India needs an average growth of 7.8 per cent, a target that fits perfectly into PowerPoint slides and policy speeches.

Read in Hindi: ‘विकसित भारत’ की चमक के नीचे थका हुआ आदमी…

But the uncomfortable question remains: where does the common man stand in this celebrated ascent? Has prosperity trickled down, or have only the graphs climbed higher while daily life has grown harsher?

The common man’s day does not begin with optimism, but with anxiety, especially about what he eats. Opening a packet of milk is an act of faith. Is it milk, or a chemical cocktail? Spices dazzle with colour but often deliver disease instead of flavour. The fish looks fresh and smells of poison. In 2025, one in four food items failed safety tests. Over the last decade, 25 per cent of samples were non-conforming, 50 per cent sub-standard, and 15 per cent outright unsafe.

In 2022 alone, over 4,300 adulteration cases were officially recorded, though the real number is widely believed to be far higher. Even model cities like Indore expose the bitter irony: cleanliness campaigns flourish, but food safety collapses. What kind of development forces citizens to swallow fear with every bite?

The second daily battle begins the moment one steps outside, on the roads: potholes, open manholes, wrong-side driving, and traffic rules treated as optional suggestions. Walking has turned into an extreme sport. In 2024, India lost 1.77 lakh lives to road accidents, an average of 485 deaths every single day, a 2.3 per cent increase over the previous year.

Uttar Pradesh alone recorded 24,776 deaths in the first eleven months of 2025, a shocking 14 per cent rise. Expressways beam down from billboards in glossy photographs, while neighbourhood roads crumble in neglect. This is the cruel paradox of macro-development and micro-pain: every citizen is an unwilling contestant on Khatron Ke Khiladi.

Healthcare, the last line of human security, is even more distressing. Government hospitals are overcrowded, understaffed, and emotionally exhausted. India has just 20.6 healthcare workers per 10,000 people, less than half the WHO-recommended 44.5. Public health expenditure languishes at a meagre 1.3 per cent of GDP. If you get medicine, consider yourself lucky; if you get timely treatment, call it a miracle. Private hospitals exist, but for the common man, they are not centres of healing; they are financial trauma wards. Illness here does not merely break the body; it drains savings and strips away dignity.

The world of work offers little relief. The average Indian works 46.7 hours a week, yet 51 per cent work more than 49 hours. Burnout afflicts 58 per cent of the workforce. Overwork has been repackaged as patriotism; exhaustion marketed as national duty. Sycophancy often pays better than competence. Respect is measured less by merit and more by designation and bank balance. Inequality hardens into a wall that grows taller by the day.

Digital India, once sold as empowerment, has become a minefield of fraud. Sixty per cent of Indians receive at least three spam calls daily. In 2025, digital scams robbed citizens of ₹26 billion. For the elderly, this ecosystem is a maze of traps; one wrong click and a lifetime’s savings vanish. Data is looted, trust shattered. One must ask: Who is technology really serving, the common man, or those preying on him?

Then there is the environment, silently screaming under the weight of ‘development’. In 2025, air quality indices in many cities, including Delhi, crossed 500, levels that border on the unbreathable. Nearly 27.77 per cent of India’s land is degraded. Over 40.7 million people are affected by extreme weather events. Rivers resemble sewers, heatwaves kill, and rains destroy. This is not nature’s revenge; it is our own recklessness coming home to roost.

The greatest tragedy is not that conditions are bad, but that we have normalised them. Dodging potholes, eating in fear, borrowing for medical care, abusing spam callers, this has become everyday life. Complaints are no longer angry; they are weary, resigned.

The dream of a Developed India will remain incomplete as long as the common man is forced merely to endure instead of truly living. Real development is visible on streets that do not kill, in hospitals that heal without bankrupting, on dinner plates that inspire trust, and in the air that can be breathed without fear. Otherwise, the glittering slogan of Viksit Bharat will one day dissolve into smog, leaving behind a tired, silent population asking a single haunting question: Is this all the destiny the common man deserves?

Related Items

Real GDP growth for FY27 is projected at 6.8-7.2 per cent

India’s ‘Unique’ Journey as a Republic…

India rises as a ‘Global Medical Travel Destination’